Kanji

The adoption of Chinese characters has proven to be the equivalent of a linguistic Procrustus bed in the case of Japanese. A highly inflective language like Japanese has a structural disadvantage, as kanji --Han Characters-- are much better suited as a writing system for languages that are similar to Chinese. Vietnamese had considerably less problems in adopting Chinese characters because it is an isolating tonal language like Chinese. Words in isolating languages are not subject to change and therefore don't need to represent aspect or time. In order to reflect morphological change, Japanese developed its own syllabaries. (Kana) Hiragana is used for grammatical particles and inflectional affixes. The other set of syllabic signs, katakana, is employed to write non-Japanese loanwords and many adverbs. As a general guide kanji are used to write most nouns, verbs and adjective bases. When early in the first millennium AD Japan adopted kanji, at that time having no script of its own, two main strategies were employed to accommodate the script to the language. Kanji were selected on the basis of meaning and in relation to the sound. This process can be represented in the following way.

Meaning--3some, 3dent, 3iary, 3ce, 3d

Sound-----3angle, 3ceps, 3cycle

The reading of kanji that relate to Japanese morphemes (the smallest semantic elements in a language) on the basis of meaning is referred to as kun-reading. The kanji was assigned a Japanese pronunciation, sometimes more than one, and chosen for the correspondence with its meaning in Chinese. Although there can be multiple readings for one kanji, it also happens that some have no kun-reading at all. The kun-reading of 流れ星 is naga(re)boshi, meteor, falling star.

The on-reading or Sino-Japanese pronunciation is an approximation of the Chinese pronunciation at the time when the kanji was introduced. At different times kanji from various parts of China were adopted, with the result that some kanji have more than one on-reading and also have different meanings. There are three distinct echoes depending on whether the word was borrowed in the sixth century, the eighth century, or early in the millennium. The on-reading of 流星 is ryuusei, meteor, falling star. As many Chinese loanwords found their way into Japanese, it was only natural to write Chinese words with Chinese characters. This created an intriguing “distortion effect” as new words were created with kanji based on an approximation of the Chinese pronunciation combined with semantically selected kanji that ignored pronunciation altogether. Sino-Japanese morphemes like these have been instrumental in enriching Japanese with an extensive layer of vocabulary. This process has been compared to the role of Arabic within Persian and Turkish or Latin within the European languages. Sino-Japanese words relate to concepts that either were not in existence in Japanese at that time or were deemed to be more refined than their native equivalent. They take the form of kanji compounds (two or more kanji) that generally follow the on-reading. Single isolated kanji usually have a kun-reading.

There are according to tradition six types of kanji that, although no longer studied because of the confusing nature of the definitions, are useful in the sense that they shed light on the structure of kanji. The first four categories refer to structural composition, the last two to usage.

Shoukei-moji 象形文字 A fraction of modern characters consists of “pictographs”, characters that purpose to be a literal graphic representation of an object. Examples of this type include tree 木, or moon月

Shiji-moji 指事文字 Ideographs or logo grams also represent a small number of modern kanji. These “symbols” essentially express a simple abstract concept like up and down 上下.

Kaii-moji 会意文字 A small number of modern kanji consists of “ideographs”, usually a combination of pictographs to present an overall meaning. An example is rest, made from tree 木 and person 人.

Keisei-moji 形声文字 The largest of the categories representing 85% of kanji, are the “semantic-phonetic” characters. Consisting of two components, the phonetic component refers to the (long obsolete) pronunciation of the character. In Japanese this is the on-reading. The semantic element indicates the meaning or context. In the passing of time the semantic context has frequently been subject to change, making the interpretation of a character in many cases rather confusing. Also, the distinction between phonetic and semantic elements of a character is ambiguous as phonetic elements frequently have semantic connotations as well. An example is mosquito that combines insect 虫 with 文 BUN to give “insect that makes a BUN sound”.

Tenchuu-moji 転注文字 “Derivative characters” or characters with borrowed meaning and pronunciation is a rather vague category. As the majority of characters have undergone some change of meaning, this particular classification is not so relevant. Sen 占 used to mean divination but now has acquired a major meaning of occupy, replacing a more complex character with the same pronunciation.

Kasha-moji 仮借 文字 “Phonetic loan characters” are employed for their sound value to represent other but unrelated but homophonous morphemes. An example is lai “barley” in Chinese for lai “come” 来

Kokuji 国 字 “Made in Japan” characters are sometimes treated as a seventh category. The number in modern kanji is small. The most famous example is 働く hataraku that combines person” 人 radical with “movement” 動 to create “work”. The character has been adopted into written Chinese in the twentieth century.

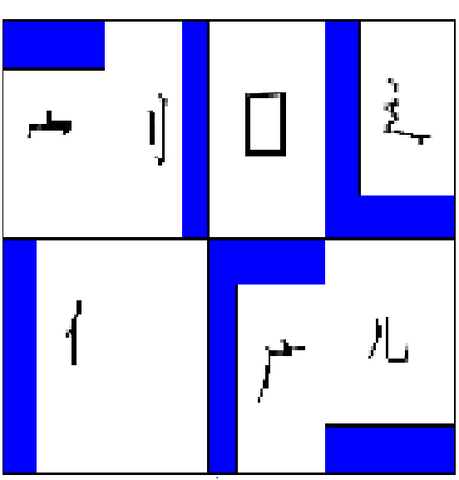

An approach that focuses on important structural aspects of kanji will reduce reliance on memorization. A clear understanding of radicals will make the learning process much more efficient. There are seven basic positions in which a radical is employed within a character.

Kanmuri (crown) ukanmuri (u katakana) 安 宙 宝, kusakanmuri (grass) 花 若 苦

Hen,ben (left side) ninben (person) 作 休 仕, tsuchihen (earth) 地 坂 城

Tsukuri, (right side) rittoutsukuri (sword) 利 判 刊, sanzukuri (three) 形 影 彫

Ashi, shita (base or foot) hitoashi (legs) 先 兄 光, shitagokoro (heart) 悪 悲 意

Kamae, (frame) kunigamae (box) 囚 図 困 mongamae (gate) 聞 閉 開

Tare, (hanging or trailing) yamaidare (sick) 病 疲 症 , madare (cliff) 広 店 麻

Nyou (L-shaped) shinnyou (road) 近 道 送, ennyou (long stride) 建 延 廷

Meaning--3some, 3dent, 3iary, 3ce, 3d

Sound-----3angle, 3ceps, 3cycle

The reading of kanji that relate to Japanese morphemes (the smallest semantic elements in a language) on the basis of meaning is referred to as kun-reading. The kanji was assigned a Japanese pronunciation, sometimes more than one, and chosen for the correspondence with its meaning in Chinese. Although there can be multiple readings for one kanji, it also happens that some have no kun-reading at all. The kun-reading of 流れ星 is naga(re)boshi, meteor, falling star.

The on-reading or Sino-Japanese pronunciation is an approximation of the Chinese pronunciation at the time when the kanji was introduced. At different times kanji from various parts of China were adopted, with the result that some kanji have more than one on-reading and also have different meanings. There are three distinct echoes depending on whether the word was borrowed in the sixth century, the eighth century, or early in the millennium. The on-reading of 流星 is ryuusei, meteor, falling star. As many Chinese loanwords found their way into Japanese, it was only natural to write Chinese words with Chinese characters. This created an intriguing “distortion effect” as new words were created with kanji based on an approximation of the Chinese pronunciation combined with semantically selected kanji that ignored pronunciation altogether. Sino-Japanese morphemes like these have been instrumental in enriching Japanese with an extensive layer of vocabulary. This process has been compared to the role of Arabic within Persian and Turkish or Latin within the European languages. Sino-Japanese words relate to concepts that either were not in existence in Japanese at that time or were deemed to be more refined than their native equivalent. They take the form of kanji compounds (two or more kanji) that generally follow the on-reading. Single isolated kanji usually have a kun-reading.

There are according to tradition six types of kanji that, although no longer studied because of the confusing nature of the definitions, are useful in the sense that they shed light on the structure of kanji. The first four categories refer to structural composition, the last two to usage.

Shoukei-moji 象形文字 A fraction of modern characters consists of “pictographs”, characters that purpose to be a literal graphic representation of an object. Examples of this type include tree 木, or moon月

Shiji-moji 指事文字 Ideographs or logo grams also represent a small number of modern kanji. These “symbols” essentially express a simple abstract concept like up and down 上下.

Kaii-moji 会意文字 A small number of modern kanji consists of “ideographs”, usually a combination of pictographs to present an overall meaning. An example is rest, made from tree 木 and person 人.

Keisei-moji 形声文字 The largest of the categories representing 85% of kanji, are the “semantic-phonetic” characters. Consisting of two components, the phonetic component refers to the (long obsolete) pronunciation of the character. In Japanese this is the on-reading. The semantic element indicates the meaning or context. In the passing of time the semantic context has frequently been subject to change, making the interpretation of a character in many cases rather confusing. Also, the distinction between phonetic and semantic elements of a character is ambiguous as phonetic elements frequently have semantic connotations as well. An example is mosquito that combines insect 虫 with 文 BUN to give “insect that makes a BUN sound”.

Tenchuu-moji 転注文字 “Derivative characters” or characters with borrowed meaning and pronunciation is a rather vague category. As the majority of characters have undergone some change of meaning, this particular classification is not so relevant. Sen 占 used to mean divination but now has acquired a major meaning of occupy, replacing a more complex character with the same pronunciation.

Kasha-moji 仮借 文字 “Phonetic loan characters” are employed for their sound value to represent other but unrelated but homophonous morphemes. An example is lai “barley” in Chinese for lai “come” 来

Kokuji 国 字 “Made in Japan” characters are sometimes treated as a seventh category. The number in modern kanji is small. The most famous example is 働く hataraku that combines person” 人 radical with “movement” 動 to create “work”. The character has been adopted into written Chinese in the twentieth century.

An approach that focuses on important structural aspects of kanji will reduce reliance on memorization. A clear understanding of radicals will make the learning process much more efficient. There are seven basic positions in which a radical is employed within a character.

Kanmuri (crown) ukanmuri (u katakana) 安 宙 宝, kusakanmuri (grass) 花 若 苦

Hen,ben (left side) ninben (person) 作 休 仕, tsuchihen (earth) 地 坂 城

Tsukuri, (right side) rittoutsukuri (sword) 利 判 刊, sanzukuri (three) 形 影 彫

Ashi, shita (base or foot) hitoashi (legs) 先 兄 光, shitagokoro (heart) 悪 悲 意

Kamae, (frame) kunigamae (box) 囚 図 困 mongamae (gate) 聞 閉 開

Tare, (hanging or trailing) yamaidare (sick) 病 疲 症 , madare (cliff) 広 店 麻

Nyou (L-shaped) shinnyou (road) 近 道 送, ennyou (long stride) 建 延 廷

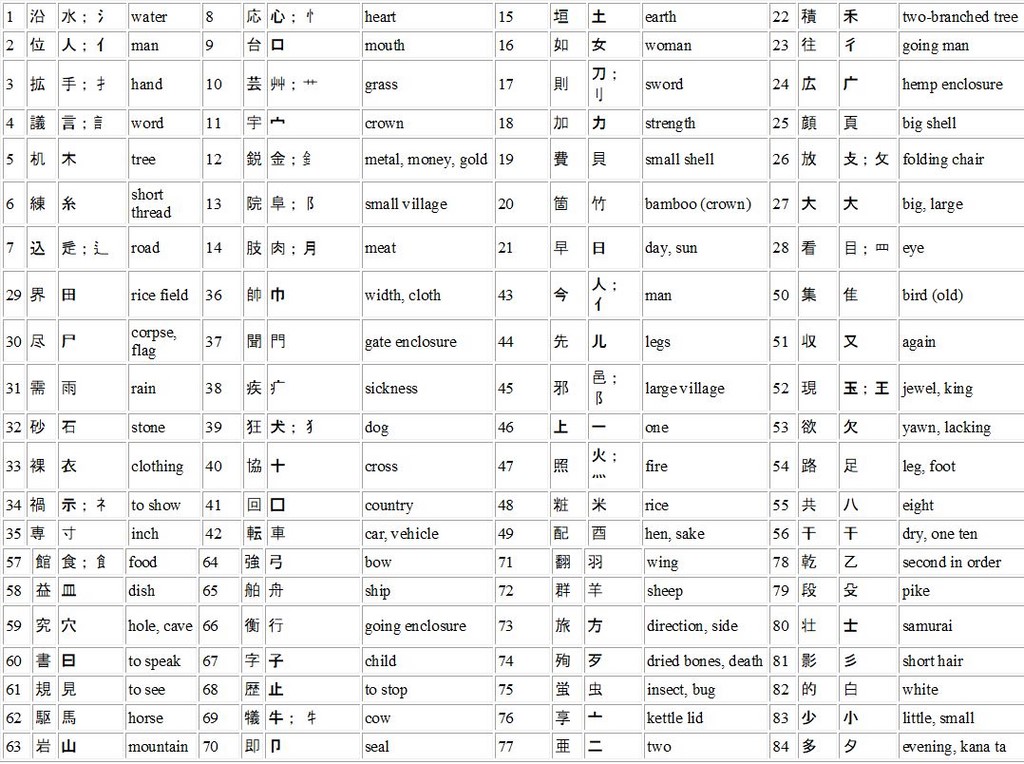

As the most frequent 24 radicals account for 54% in the General Use Kanji, memorizing these elements will bring considerable benefits. The 84 radicals have been arranged in order of frequency which means that the first half of the series will feature much more often. In the majority of cases the interplay of radicals with signature characters will be the most salient feature in the learning process.